Do you know: What is Theory of Constraints? A survey performed just a few years ago showed that 90% of people involved in operations or project management know what Theory of Constraints (TOC) is. But, when they were asked to explain how TOC works in the manufacturing plant, or precisely how it applies to multi-project environments, fewer than 10% could accurately describe it. Theory of Constraints might not have reached common knowledge and practice yet, but it’s a proven strategy that’s simple to use, and easy to apply to daily life on the shop floor or other parts of the business. Furthermore, most people use several aspects of Theory of Constraints in their personal and professional lives without realizing it!

Theory of Constraints is a methodology to improve the performance of a system. But to understand it fully, let’s step back to the beginning. Close to fifty years ago, an Israeli physicist named Dr. Eliyahu M. Goldratt put forth a theory that the performance and output of a system is often determined by a single resource (a constraint) within that system. By identifying and properly managing that constraint, managers can significantly, sometimes spectacularly, improve the performance of the entire system. The Theory of Constraints was born, and it became widely known when Goldratt published a book called The Goal in 1983. In recent years, The Goal has still made its way occasionally to the top of the New York Times’ best-selling list of business books. The Goal tells a story about a plant manager named Alex Rogo, whose facility is going to be shut down unless he drastically and quickly improves plant performance. In the story, Rogo goes through a socratic learning process about what matters most in his factory, and what is preventing him from hitting strategic and financial objectives. Before his passing in 2011, Dr. Goldratt labeled the work surrounding his Theory of Constraints as “uncommon common sense.”

Theory of Constraints is a methodology to improve the performance of a system. But to understand it fully, let’s step back to the beginning. Close to fifty years ago, an Israeli physicist named Dr. Eliyahu M. Goldratt put forth a theory that the performance and output of a system is often determined by a single resource (a constraint) within that system. By identifying and properly managing that constraint, managers can significantly, sometimes spectacularly, improve the performance of the entire system. The Theory of Constraints was born, and it became widely known when Goldratt published a book called The Goal in 1983. In recent years, The Goal has still made its way occasionally to the top of the New York Times’ best-selling list of business books. The Goal tells a story about a plant manager named Alex Rogo, whose facility is going to be shut down unless he drastically and quickly improves plant performance. In the story, Rogo goes through a socratic learning process about what matters most in his factory, and what is preventing him from hitting strategic and financial objectives. Before his passing in 2011, Dr. Goldratt labeled the work surrounding his Theory of Constraints as “uncommon common sense.”

Why Theory of Constraints

Manufacturing companies, in particular, care about the Theory of Constraints because it provides a systematic approach to identify and address the most critical limiting factor, or bottleneck, in their production processes. By focusing on this constraint, plants can significantly improve their overall efficiency and throughput. Implementing TOC often leads to reduced lead times, lower inventory levels, better on time delivery performance, and higher profitability. Additionally, it fosters a culture of continuous improvement, since teams are encouraged to constantly seek out and eliminate new constraints. Ultimately, the Theory of Constraints helps manufacturers achieve more with their existing resources, driving sustainable growth and competitive advantage.

How to Do Theory of Constraints

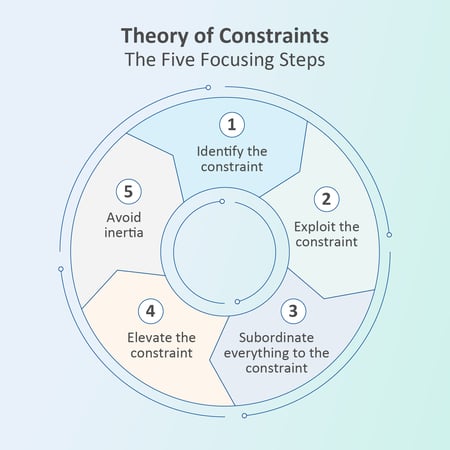

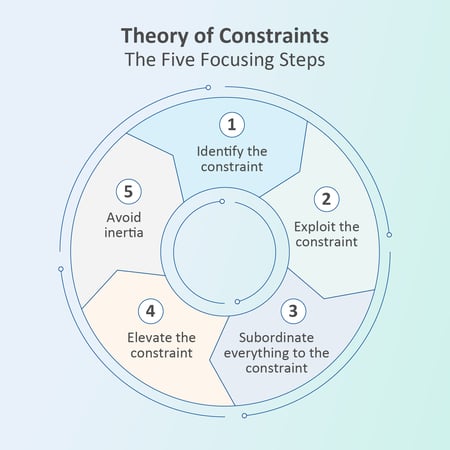

Dr. Goldratt created the Five Focusing Steps as the foundation for the Theory of Constraints. It’s a cyclical process he prescribed to identify and eliminate constraints. The Five Focusing Steps process can be used in different areas or domains. In order, they are:

- Identify the constraint

- Decide how to best exploit the constraint

- Subordinate everything to the constraint

- Elevate the constraint

- Avoid inertia (e.g., go back to step one)

According to the Theory of Constraints methodology, it's impossible to improve the performance of a system without properly identifying where the constraint is (step 1 – “identify the constraint”). In many cases, there is just one constraint in the system. If there are multiple constraints or if the perception is that there are multiple constraints, one of two things is happening. The first is that the system has multiple subsystems that are separate and independent — each one of those subsystems has a constraint. The second is that some of the constraints are self-created.

A great example of self-created constraints is in manufacturing, when the shop floor releases products too early into the product flow, which creates a wandering bottleneck, also known as a floating constraint. A floating constraint isn’t a true constraint. It’s probably the consequence of a policy to keep people busy on the shop floor. And it’s self-inflicted or self-created. When step 1 is complete, the five focusing steps process continues, then repeats continuously — it’s a structured continuous improvement approach that delivers quantifiable, sustainable results.

Who Uses Theory of Constraints

Dr. Goldratt asserted four applications of Theory of Constraints, which are well-known throughout industry and the business world —

For manufacturing companies, drum-buffer-rope (DBR) is a scheduling process to maximize throughput. The "drum" sets the pace of production based on the system's constraint, the "buffer" protects the constraint from disruptions by maintaining a small inventory, and the "rope" synchronizes all other processes to the drum's pace. This method helps in maintaining a smooth workflow and preventing bottlenecks, ultimately enhancing overall efficiency.

For project management organizations or groups, critical chain project management (CCPM) is a method to manage project schedules by addressing resource constraints and uncertainties. Unlike traditional project management, which emphasizes task order and deadlines, CCPM prioritizes the critical chain—the sequence of dependent tasks that determine the project's duration. By incorporating buffers to account for uncertainties and ensuring resources are available when needed, CCPM aims to reduce project timelines and improve reliability.

The distribution solution for distribution companies or organizations focuses on optimizing the flow of goods from production to the end customer. It aims to reduce inventory levels and improve service levels by synchronizing supply with actual demand. This approach uses buffer management to ensure that stock is available where and when it's needed, minimizing delays and excess inventory.

Conflict resolution and the thinking processes for HR and other human or organizational domains involves identifying and addressing the root causes of conflicts that hinder progress. Practitioners often use a technique called "evaporating cloud," which helps to uncover underlying assumptions and find win-win solutions. By resolving conflicts effectively, organizations can remove obstacles that limit their performance and improve overall efficiency.

At a high level, the four domains — manufacturing, project management, distribution, and HR/organizational — are where TOC performs best and produces the most spectacular results. And, there are many organizations that have a mix of the four domains, not just one of them.

For example, a lot of engineer-to-order manufacturing companies also have heavy project management activities. This is especially true in engineering, for the process of developing new products — that usually involves a lot of research, development, and engineering.

Then the critical chain project management methodology could be used as a first step before a product becomes a standard product. Later, manufacturing would apply drum buffer rope to manage operations. Finally, most organizations could benefit from the thinking processes. That includes large companies and small, those in industry or financial companies, even non-profits, services businesses, public agencies, and anywhere people work. In fact, anyone can apply the thinking processes in their personal life to enhance the effectiveness and enjoyment of their interpersonal relationships.

When Execs Ask: Are We Ready for Theory of Constraints?

Even though there’s a lot to be gained by using Theory of Constraints, managers and executives usually wonder if the organization is even a good candidate for it.

The biggest criteria to assess readiness is to identify if the company is open to change and willing to change, or even “has to change.” Unfortunately, the latter is often the greatest driver — if things don’t change, something bad will happen. For plant manager Alex Rogo, the main character in the story in The Goal, things were pretty desperate. If he didn’t improve operational performance, his plant would be shut down, sold, or some other awful thing. Bottom line – you have issues to fix, and you’re motivated to resolve them.

The next readiness criteria is know-how — either the kind that comes from your own studying and reading, or from a knowledgeable Theory of Constraints practitioner. When deciding who will guide your organization through the process, make sure they have practical experience with Theory of Constraints in your specific industry.

The final readiness criteria are discipline and authority: Practicing the focusing steps with consistency requires determination. The depends on your authority to do so. When a manager lacks the authority or ability to inspire or require change, the initiative can become stagnant and unproductive. It usually leads to a decline in morale, since employees feel their efforts are futile and their potential for growth is stifled.

If your company is ready to learn or apply Theory of Constraints, here are some early steps to get started:

- Designate a team lead and an executive sponsor.

- Decide if your company needs an outside resource.

- Foster a culture of continuous improvement and open communication.

- Encourage participation.

- Make training and education accessible to all who desire or need it.